News

Geospatial technology moves mainstream in agriculture - and now offers benefits to some of the world's poorest communities

Geospatial technology has emerged as a powerful tool for the collection, management and analysis of agricultural information over the last couple of decades and its applications are far reaching. In the Huffington Post this month, contributor Brian Milne highlighted a competition launched by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Microsoft in mid-July, asking software developers to create applications to utilise more than 100 years of agricultural data to explore how the US food system can achieve better food resiliency.

To aid the process, USDA made a significant amount of information available to the public for the first time, including a vegetative condition database compiled from satellite data and geospatial data sets detailing annual land cover. Milne wrote: “If we’ve learned anything in the agriculture industry in recent years, it’s that climate change and extreme weather patterns are the new reality - and all of us have to plan accordingly to help ensure the safety of our food supply. Developers included.”

See links:

- Hackathon Challenges Developers to Make a Difference in Agriculture

- Help build a sustainable US food system by putting USDA data into the hands of farmers, researchers, and consumers

- USDA/Microsoft “Innovation Challenge” Offers $60K in Prizes to Software Developers

Participating developers will no doubt rise to the challenge and come up with exciting, new applications (they’ll be motivated by a US$60,000 prize pool), but as technology and innovation marches on, basic geospatial analysis is also finding applications in some of the world’s poorest and most deprived communities. Prime Consulting International Ltd has been using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Global Positioning System (GPS) units to help understand and control outbreaks of brucellosis in sheep and goats in rural Afghanistan since 2011.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by bacteria. Animals that are most commonly infected include sheep, cattle, goats, pigs and dogs, CDC says. “People can get the disease when they are in contact with infected animals or animal products contaminated with the bacteria.” This was the case in Bamyan Province when Prime arrived in 2011. It picked up on the disease through the region’s public health system, which was showing human infection rates in some parts of the province that were amongst the highest seen anywhere in the world.

Dr Mohammad Haider, the Bamyan Provincial Veterinary Officer, explains the brucellosis programme.

Brucellosis does not circulate in people, but locals - particularly children and women - were contracting it from birthing fluids during sheep and goat abortions, or from eating and drinking contaminated milk products. Since 2011, Prime has been working with the livestock services department of Bamyan’s Department of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (DAIL), along with private veterinarians, to halt the spread of the disease.

Prime director Dr Alan Pearson was an early adopter of GIS in agriculture and animal health in the early 1990s, as project leader for the development of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture’s AgriBase national spatial farms database (sciquest.org.nz/node/62221). In 2011, he took on a lead technical role in Prime’s ongoing Afghanistan Agricultural Support Programme (ASP), drawing on his earlier knowledge of geospatial technology to inform targeted control of brucellosis in Bamyan. Key to this was first understanding the geographic spread and prevalence of the disease through the use of GIS with the help of Dr Eric Neumann, a veterinary epidemiologist specialising in disease management, biosecurity policy, livestock production and global trade in animals and animal products.**

Dr Alan Pearson describes the livestock services capacity building component of Prime’s ongoing Agricultural Support Programme (ASP) in Bamyan Province, Afghanistan.

In Bamyan, sheep and goats are crucial to village life. Cattle and donkeys are farmed too, but not to the same extent. Dr Neumann says most farming families get by “pretty well year on year”, living subsistence lifestyles, but “there’s no back up. They have no capacity to absorb [a disease outbreak]. Brucella really takes the guts out of a village. While it rarely causes death [in humans], it’s a long-term debilitating disease”. In countries with developed livestock and public health systems, such as New Zealand, it is not a hard disease to eradicate. “There’s a list of eight to 10 to 12 [diseases] that the world worries about in these developing countries,” Dr Neumann says. “The buzz term is neglected zoonotic diseases.” Brucellosis is one of those. Others include rabies, leptospirosis and tuberculosis.

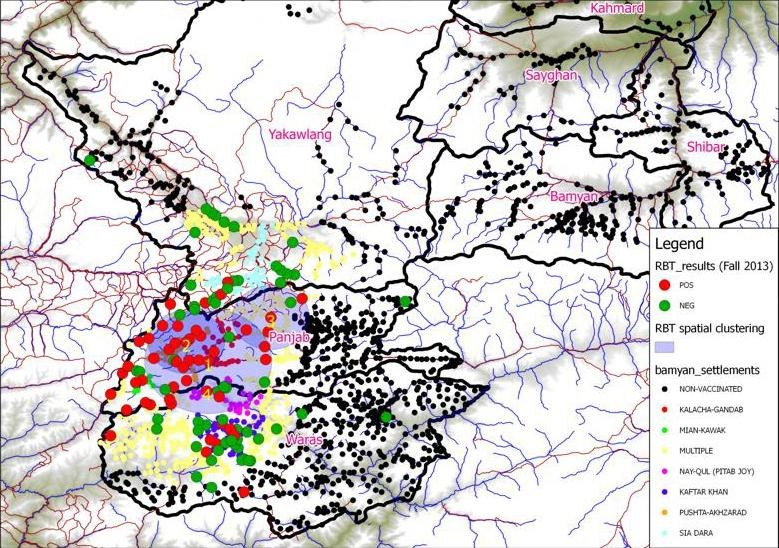

A map showing Brucellosis spread and prevalence in Bamyan Province, Afghanistan. Red dots indicate villages with at least one seropositive (infected) animal. Green dots indicate villages with no seropositive animals.

In Bamyan, farmers were losing stock to “abortion storms” in the winter, at a time when sheep, goats and humans were living in close confines. “The tipping event is often in the winter because sheep and goats give birth in spring. Abortion events [are] often mid-gestation,” Dr Neumann says. In winter, sheep and goats are often housed on the bottom floor of human dwellings, protecting them from the elements and creating warmth for family members upstairs. They’re tightly packed and the spaces are not well ventilated. In the event of an abortion, humans risk contamination via contact with birthing fluids and or from handling the aborted foetus. Other, healthy animals are also exposed.

To understand the spread of the disease, Prime gave Afghan locals simple GPS units, trained them how to use them and sent them out into villages across four districts. This information was used to create a map of infected and high risk areas and helped Prime decide how to allocate a supply of brucellosis vaccine imported from Jordan. “The highest prevalence of disease was focused around the major road used by traders to supply livestock from western provinces to population centres like Kabul,” Dr Neumann says. “We would not have stumbled upon [that sort of risk factor information] without the use of mapping tools.”

Since 2011, farmers have reported fewer abortions in their sheep and goats during the high-risk winter periods and there has been “no further expansion of the disease into previously identified low prevalence regions”, Dr Neumann says. “The number of human brucellosis cases appears to have stablised; they were trending upwards significantly when we got in the area. We’ve tried to work with the local people as best we can.” To date, the vaccination work has been supported by New Zealand and British aid funding. In future, farmers may have to pay for the Brucella vaccine themselves - a daunting but not impossible prospect. The hope is that they now see the value in it.

Delivering chilled vaccine stocks to the field teams.

**Dr Neumann has also been working with fellow Prime consultant Milou Groenenberg to build an information system to track the spread of American foulbrood (AFB) disease in Bamyan bee hives. Ms Groenenberg is managing an apiculture project aimed at improving the livelihoods of rural women through beekeeping. AFB wipes out infected hives and is spread by bees and humans through the movement of contaminated hives and equipment.

For further information, contact Dr Eric Neumann (eric@primeconsultants.net).

To read more about the Afghanistan Agricultural Support Programme (ASP) click here